On Tuesday, July 9, eleven pages of encrypted messages between Rosselló and high-ranking officials were released. Thousands of Puerto Ricans filled the streets in San Juan. On Saturday, the Center for Investigative Journalism released nearly 900 additional pages of leaked documents, reiterating what Puerto Ricans already know from colonial rule, disaster capitalism, neoliberalism, and repression of popular uprising: the ruling elite of the Island have no regard for the life and dignity of Puerto Ricans. Shortly before midnight on July 24th, Governor Ricky Rosselló announced his resignation (scheduled for August 2nd). Inspired by the Arab Spring and other uprisings, sectors of the mobilizations have since increased their demands, calling for further resignations and envisioning a reorganization of Puerto Rican society along “anti-chat” lines (discussed below) and beyond.

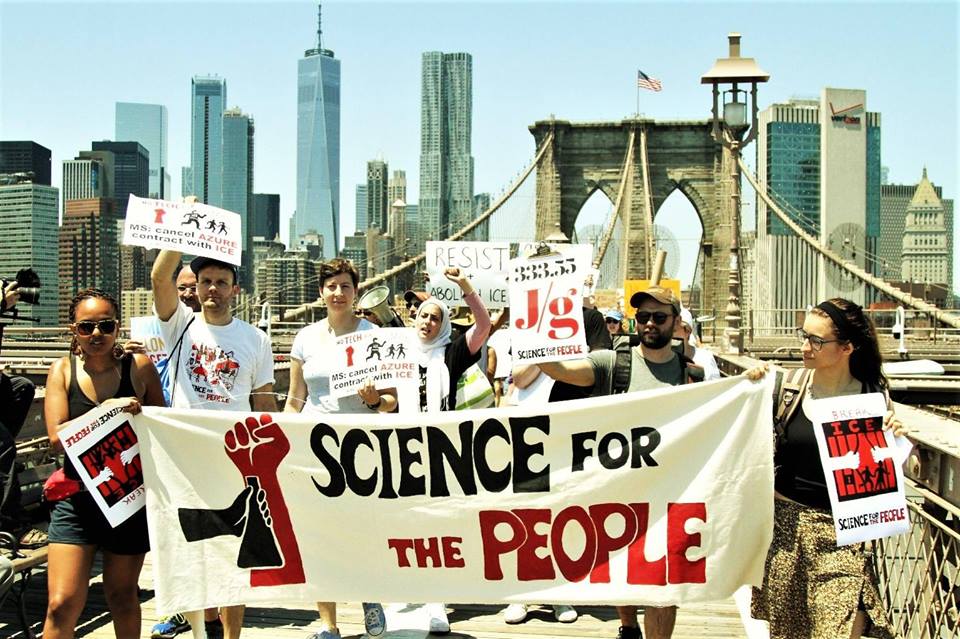

On July 25th, Science for the People’s Puerto Rico Working Group (Science for Puerto Rico) sat down with two members of the coalition JunteGente to talk about the popular uprising, its significance, next steps, and what we can do from outside Puerto Rico to support this historic moment and its escalating demands.

Bernat Tort is a Philosophy of Science professor and a performance artist. JuanCarlos “Juanqui” Rivera Ramos is a sociologist and activist from San Juan. Their science activism focuses on popularizing scientific ideas while fighting against pseudoscience and the oppressive uses of science. Both are active organizers in JunteGente.

Founded in 2018, JunteGente is a space for the convening of community organizations working against austerity, neoliberalIsm, and disaster capitalism towards a just, sustainable and solidary Puerto Rico. Their work is motivated by the question: what can we do together that we cannot do alone? As Bernat describes, “it is a gathering to think of the country we want, like a leftist wish-list. One of our aims is to mobilize in order to be prepared for moments of uprising precisely like the one we are living. When these openings occur, we want to be prepared to mobilize towards realizing our ideas.”

Please note that the complete video-recorded interview can be found below, at the end of the transcription.

Science for the People: Congratulations on Rick Rosselló’s resignation announcement last night after 14 days of continuous protesting. What was it like to receive that news, shortly before midnight? I imagine you are both sleep-deprived! What did the streets look and feel like last night in Viejo San Juan?

Bernat: Yesterday was Juanqui’s birthday so we really upped the celebration. Now every meeting with friends is a political meeting. Everyone is pumped about what we’re going to do afterward, with ideas of where we are going to go from here. At around 10 or 11 pm I went home, thinking it wasn’t going to happen. When I get home, I hear honking on the streets. I say “Shit! He did it!” and I started watching the announcement on TV. I got in the car with my partner and we went straight to Old San Juan. We were in a traffic jam of people honking their cars with the Puerto Rican flags all over and people running through the streets. It was the feeling that people got used to the fact that the streets are ours. People were walking in the middle of the main highways as if it were normal because we had non-stop protesting for two weeks. When we got to Old San Juan, people were singing and chanting. Everyone was happy and congratulating one another. It was a very festive feeling of true accomplishment. It was beautiful. We got back home at around 4 am.

Juanqui: You know, yesterday was a very strange day because the news outlets had announced that the Governor was going to resign and deliver a message to the people before noon. This was not just rumors but the main newspapers began to announce this. Outlets in the US were also saying this. Everyone was expecting the Governor to resign before noon. There was even a press conference convened at 11 am. The international news teams were physically there, waiting for the announcement. Some news even said the governor had left Puerto Rico on a plane the night before. It was a very strange day. We were tense because we thought this was yet another example of “cogernos de pendejos” [take us for fools/idiots]. We thought ‘this is horrible. We’re gonna be MORE mad now and tomorrow we’re gonna fight this even stronger.”

Bernat: And actually, they knew [an escalation] was the probable effect because they tripled the number of fuerzas de choque (riot police) in San Juan. They thought “Ok if this guy doesn’t announce something, there is going to be a huge riot.”

Juanqui: It was just before midnight that the Governor decided to resign. Once that happened, around 11:55 pm, it was like a permanent echo of yelling, chanting, screaming. The city was alive. People were throwing fireworks and, curiously, this coincided with a perreo combativo. The creativity of the protests have been amazing. Yesterday, in front of La Fortaleza (Governor’s House) and in front of the Cathedral, there was a National Perreo Combativo. I mean the party was amazing. When the Governor resigned, it was like a carnival. July 24/25 will be definitely be remembered.

Actually, July 25 is already an important day for us because of the US Invasion and the foundation of the Estado Liberal Asociado beginning in 1952. July 25 also marks the anniversary of the police assassination in 1978 of two young independentista militants in Cerro Maravilla, in the mountains of Puerto Rico. They were set-up by the police and killed. The fact Ricky resigned on July 24th and 25th is interesting because it gives another layer of symbolism and meaning to popular struggle in Puerto Rico.

Science for the People: Before discussing next steps the causes of the protests. News outlets in the US had a hard time explaining the causes and timing of these protests in a contextualized way. What are the different elements motivating people from different backgrounds to protest? What brought people out of their homes and into the streets for 14 days?

Juanqui: There are many answers to this question and honestly we will have to answer it on a continuous basis. That said, the leaked chats synthesized a great deal of the structural violence that Puerto Ricans have experienced at least- at least– since 2006. I say “at least” because we can go back to 1898 or before, of course. But since 2006 we have experienced an economic depression in Puerto Rico which deepened with the 2008 economic crash in the US and around the world. Since then, we have had a demographic hemorrhage. Hundreds of thousands have left the island archipelago. Next year we’re going to begin the Population Census which, in Puerto Rico and in the US, is gathered every 10 years. I wouldn’t be surprised if we have less than 3 million people at this point. Last decade we were 3.8 million. So we have the economic crisis, followed by the fiscal crisis, followed by the PROMESA Law which forced us to have a Junta.

Bernat: The official name is the Fiscal Oversight Board but everyone in Puerto Rico calls it the Fiscal Control Board. In Spanish, la Junta de Control but the official name is the Junta de Supervisión.

Juanqui: Right. So this Junta is imposed by Congress, with members that are not elected by anyone. It’s like we have our own IMF– but just for Puerto Rico through Congress. It basically pushes an IMF structural adjustment agenda on Puerto Rico. On top of that, you have two hurricanes: Maria and the incredible corruption in the two parties that have ruled Puerto Rico for the past 70 years. These are all variables that motivated people onto the streets.

And then you have the youth and their motivations. First, the sheer number of young people that have participated in the protests is just amazing. These are teenagers. We’re talking about 14 year-olds, 16 year-olds, 18-year olds, as well as, of course, youth in their 20s. These are folks that were born and grew up in a place where they see no future for themselves and where their parents have had to work 2-3 jobs for them to have education, food on the table, and a roof. Some of them don’t even have a roof- some have blue tarps because they lost their home to the Hurricane or they are sharing homes with their relatives.

Bernat: The lifestyle of Puerto Ricans in this past decade and a half has been transformed. And for those growing up in Puerto Rico, there is just a different consciousness. Even those who have been doing political work for a long time are finding that this moment is a revelation.

Juanqui: If someone tells you that they know what is happening, they are lying to you. If someone tells you that there is someone leading this process, that there is an organization leading the mobilizations, they are also lying to you. We are all trying to understand what’s happening even as we are actively participating.

That’s one aspect. Then you have communications. It’s true that people are suffering economically but most people have access to cell phones and they are informed in their own way, through their own mechanisms of communication. Honestly, that is a very important aspect of the mobilization.

Bernat: I mean— the meme production! The number of memes that have been produced is absurd.

Juanqui: Our lack of political representation means that our popular representatives are often our musicians, social leaders, media personalities, etc. I don’t know about other societies but here popular influencers have a massive symbolic capital. I’m not even talking about very famous people like Ricky Martin who were very involved as well. I’m talking about people like Rey Charlie– someone who all of a sudden became a leader of los barrios. This is a guy who mobilized thousands of motorcyclists from the working-class barrios, from the projects. Did you see this? I’m talking about thousands of motorcycles in the night rumbling.

Bernat: —like four thousand motorcycles! When I saw the image I said, “holy shit we have a cavalry!” Last Wednesday, July 17th, we were having a political meeting in one of the plazas. Suddenly we see people running away from tear gas, and some 50 motorcycles going towards the tear gas. We were like “Hell yeah, ok these people got our back”.

Juanqui: So, this was a popular rebellion full of creativity, democratic, and without a single death. The police shot a ton of rubber bullets and there were injuries but there was not one recorded death.

Bernat: But back to context because it was one thing after another. In 2009, under Governor Luis Fortuño Law 7 was the first hard blow to the working class. It was a law that permitted, under a fiscal state of emergency, mass lay-offs of career government employees who until that day had known job security. We’re talking about 35,000 families who were suddenly facing unemployment. In some families, both parents were government employees. That started a huge migration. Families faced the real roughness of the inability to pay rent and utilities– there was a spike in utilities, in particular, electricity. That was the context BEFORE Promesa. So when you get PROMESA it’s like “Oh Cmon”.

The austerity measures included pensions, healthcare plans, the university budget that got cut in half, the closing of schools, the passing of a $4.25 minimum wage. So when Juanqui says these kids were born in a country with no future, it’s in a literal sense. They’re not going to have free and quality education like the UPR has the potential to provide, they’re not going to have well-paying jobs. Law after law was engineering Puerto Rico to be a service society for tourism, millionaires, and tax evaders. Law 20 and 22 are designed to attract millionaires to come and establish their businesses here. As long as they create at least two jobs and live here for six months, they gain access to this fiscal paradise. Law 20 and 22 were both passed in 2012 under Governor Luis Fortuño.

Bernat: And it’s about more than being poor. Four generations ago, people were poor but there was some social mobility through public education, etc. This is a generation that knows they’re going to be worse off than their parents. And their parents are impoverished and losing whatever labor conditions and job security they had. Those are the kids we’re talking about. Those are the kids on the streets.

Juanqui: It’s very important to understand the way these laws were experienced and lived. People started to see all these billionaires moving into Puerto Rico–mostly white Americans buying a lot of land, amassing properties, and gentrifying working-class neighborhoods including via AirBnB like these barrios are some tourist commune.

Bernat: We sustained the weight of all this. So what was the breaking point? In what sense were the chats the straw that broke the camel’s back? People in Puerto Rico are so used to corruption– during elections, we would argue, “Hey, why vote for these people who are from the party of members arrested for corruption?”. They reply, “well but at least they do things…they spread around the crumbs”. What the chat revealed is that not only are these politicians corrupt, they are morally corrupt. I think there was a lot of moral outcry in the sense that it was against the dignity of Puerto Ricans. What do I mean? An example was when they said “cogemos de pendejo hasta los nuestros” ….which means “we fool even our own” although “fool” doesn’t begin to capture the strength of the word pendejo. Another chat message said “I see the future for Puerto Rico. It’s beautiful- it has no Puerto Ricans”.

The beauty of the chat was that it offended everyone. There was misogyny, violence against women, violence against obesity, homophobia, disdain for the dead. That went right into the heart of Puerto Ricans. You don’t fuck with our dead. People who had to bury their own dead during Maria, some had been silent because they said ‘well, the whole country was under strain, it was a disaster’. But they carried that hurt. When the chats were published they said, “Ok, this is too much”.

Science for the People: That said, there has been no shortage of outrageous moments in Puerto Rico even just in the past few months. What factors led to sustained protesting and what can be learned from them?

Bernat: There is a lot of contingency surrounding future planning because, as Juanqui said, there were no specific leaders. Of course, we shouldn’t underestimate the effect of sustained protests for years. For example, one of the demands being called for by some organizations is amnesty for all the protestors since the PROMESA protests began. The memes are saying: “you see? the pelús [hairy communists] were right! Everything they protested for was right. It’s all there in the chat– now you know it’s true and that it wasn’t just leftist paranoia”. So we cannot underestimate that effect of sustained protests for years.

To give you one example, the Colectiva Feminista had a plantón in December 2018. They said, “we’re gonna sit here in front of Fortaleza [the Governor’s Mansion] and we’re not going to move until you declare a state of emergency for gender-based violence”. Even though it didn’t work in terms of beginning a dialogue with the government, it did get coverage in the news and people all over started speaking about feminicide. There was a very horrible case of a teenager who lit his ex-girlfriend on fire. He poured gasoline on her and well, suddenly this time it became a national topic. The same thing happened with the pensions and with the dead bodies movement. These movements have been doing very important and untiring work and now their demands are part of peoples’ vocabulary. You cannot underestimate that bricklaying work. But that’s not to say this is the reason why these particular chats led to unending protest for two weeks. I have no answer. We’re all just as surprised as you are. We’re living that history but we’re trying to understand it just as you are.

Juanqui: There’s another thing. This may sound stupid but it’s the summer. Most people are working but the youth are out of school. I say most people are working but it doesn’t mean they have formal jobs. They work in the informal economy and many people have several jobs para ganarse la vida. On the other hand, some of these jobs, although precarious, are more flexible. The Center for Investigative Journalism did a great job because they didn’t just publish the leaked chats to people and media outlets, they also wrote documents analyzing the chats. Every day you had new material analyzing different aspects of the chats. Jay Fonseca is another figure that, while not a radical or intellectual, is a figure some people listen to on the radio and every day he reported on a different piece of the chat.

You have to understand that this was a really fun struggle. There is just something about el goce [the joy] that has been absolutely incredible! I mean, las convocatorias [calls to action]! This is what I mean when I say that this was not planned. People were literally inventing convocatorias like “tomorrow we’re gonna be in perreo militante!” —and people just went. Organizing an action was as easy as making a social media post and that’s it. Mira, our biggest mobilization EVER in Puerto Rican history: it was convened by some person and folks just ran with it. There were six different posters made for the same activity. We didn’t even know the route of the march. Nobody knew cómo carajo we were marching but it worked! It’s really interesting. But it all has to do with el goce. And there are lots of examples like this: one action was to do yoga in front of La Fortaleza at 6am. Hundreds of men, women, and children doing yoga to protest!

They also did Rogativas. La Rogativa is a legend based on a supposed attack on the British in the 18th century. In the legend, men, women, and children carried torches and scared away the British. In reality, in history, the attack was led by cimarrones who lived on the coast. But anyhow, people protested in all forms–from yoga to torch marches.

Bernat: To give you another example of how something outrageously offensive was turned into something positive: as you know, in the chats they called Melissa Mark-Viverito a whore. Suddenly there were lots of women with “PUTA” written on their bodies, going naked to the protests, with the PR flag painted on their body. There was a convening of strippers saying: Somos putas pero no corruptas (we are whores but not thieves) and they marched with their stripper clothes. It was beautiful. This was the creation of what Juanqui has called ‘the anti-chat’. The chat was the negative iteration of all these claims and people transformed their meaning via appropriations into the anti-chat, which is the positive and powerful appropriation of all the chats saying “we are here and you do not represent us”.

Juanqui: The streets reflected the diversity of our bodies, sexualities, gender identities, and even our ideas. To define the “dominant ideology” of this movement is very difficult. Maybe we can look towards the “anti-chat” to elaborate a platform of the people. Oh, you hate the poor? Well, carajo, yeah we’re poor and we need a political program that can help transform this reality and the conditions that created poverty in the first place. Oh, you hate fat people? Fat people organized and marched with shirts that read: “este gordito tu no lo coges de pendejo” and “éste no es el gordo que te perdonó.” That creativity is part of the reason the marches were sustained, although in a larger sense it really is a mystery how this all played out. We’re all still trying to understand while at the same time being involved in the everyday struggles because that’s where we have to be. You have to be there not just to understand but to have a political effect.

Science for the People: What are the most significant elements in the nearly 900 pages of leaked documents?

Bernat: Two chat messages in particular sum up the others pretty well. The first one is: “we foresee a beautiful future for Puerto Rico, one without Puerto Ricans,” and the other is “cogemos de pendejos hasta los nuestros” [we fool even our own].

Juanqui: There’s another one where the Governor is making fun of poverty; of poor houses that were torn down by the hurricane. That is crucial. One that topped the glass was the mockery of the dead that said “don’t we have some cadavers we can toss to our vultures?” When they fuck with our dead, people really feel it. On the streets we try to ask people “Why brought you out here?” and many would say they have dead family and they’re making fun of our dead. They use the hurricane financial aid for their own political campaigns. Dignity has a lot to do with the power of this battle.

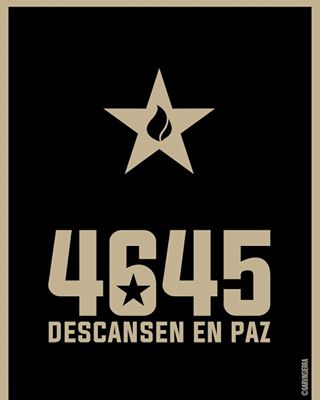

Bernat: Look at this meme. It says “our 4645 deads can rest in peace”. As if to say, “ok we did it. Now you can rest in peace because we kicked this bastard out.”

Juanqui: When Trump came to Puerto Rico after the Hurricane, the Governor told Trump that we had only 16 deaths. Trump said, ‘ah this isn’t a tragedy; Katrina was a tragedy’. Then came the Harvard study, where that number, 4645, comes from. Then, the government asked for a different study, and they came up with half of that number. Then the Harvard study said they had been very conservative in their estimate. In any case, the number that stayed was 4645 and you could see it everywhere in the protests: banners, graffiti, 4645 everywhere.

Bernat: Maybe it didn’t get much international attention, but one of the most beautiful protests after Maria, involved people asking others to bring shoes of the dead ones to the Capitol buildings, in order to get 4645 shoe pairs. They wanted to collect their stories of the dead so they started doing interviews. It was very powerful. People really felt it. It was the most beautiful symbolic political protests after Maria.

Juanqui: The government never officially did anything. They didn’t even recognize the number of deaths. They didn’t make a memorial, a tribute, nothing, nada, nothing.

Bernat: Something important to understand that you hear people saying frequently is, “yeah, I got mad about the chat but it’s not about the chat”. People have been very quick in making the jump from being offended by “puta” to saying “we have real problems. It’s not that you called me poor, it’s that I *am* poor, and it’s a systematic issue of mismanagement of funds.”

There’s a very famous, telling set of photographs side by side. One is during Hurricane Maria in Curacao, one of the hardest-hit towns, with people who spray-painted on the street “we need water- we are dying of thirst- HELP” so that helicopters could see them and bring water. Next to this image is another image of thousands of boxes of bottled water that was brought here via help from the diaspora and other international efforts. They had it in an empty, they never delivered them— purposely, so that people would go out and buy water. Everyone has seen those images, everyone knows.

I know that Jean Baudrillard didn’t mean it this way when he said ‘the transparency of evil’ but here very literally evil was transparent. It was like “holy shit these people care NOTHING about us.”

Science for the People: Before diving into the uprising’s concrete demands, what does the organizational landscape look like? Who are some of the organized actors involved?

Bernat: Jornada: Se Acabaron las Promesas (sort of our black bloc in Puerto Rico);Colectiva Feminista; CAMs- Centros de Apoyo Mutuo (they’re huge because they don’t have a center, they’re decentralized, with different representations); some people from the independence party; IDEBAJO-Iniciativa De Ecodesarrollo De Bahia De Jobos (a regional community initiative especially active in the south around energy issues- they’re also the main organizers against the dumping of the ashes in the Bahía area); militant lawyers (who were on the streets 24/7 against police brutality and repression), Güakiá (the agro-ecological group that hosted your solidarity brigade last summer); Auditoría YA- Frente Amplio por la Auditoría de la Deuda (the debt auditing effort); Federación de Maestros; CasaPueblo; UTIER (the electricity union), and several others…

Science for the People: Ahora sí, what were the concrete demands of the protests and how they coalesce? What political openings did those demands create? Are there demands that were left out or that you personally think would have been important to include?

Bernat: Beyond the Rosello resign, a popular one is “Ricky, renuncia y llévate a la Junta” (‘Ricky, resign and take the Oversight Committee with you’). The demands [speak to] a broader problem: we are living in an undemocratic and corrupt [society] by design. The PROMESA law has provisions that state committee members can be legally bribed. They can get benefits from doing different deals with different institutions. It’s legalized corruption. El colmo del descaro.

What some people are discussing is that if someone from Ricky’s own party substitutes him, nothing really changes. The changes we favor include electoral reform, that could go in the direction of referendos recursatorios to facilitate kicking someone out. We could also have two cycles of elections, allowing coalitions of minority parties so they can negotiate a shared government. Proportional voting as well, if a party gets 20% of the vote, they get 20% of the government and so on.

Science for the People: Are these popular demands? How much support do these and other demands have?

Bernat: The organizations we’ve been working with all agree to most of these demands. Today begins the hardest part of the organizing. Regarding elections, there are also demands to audit the debt, repeal the PROMESA law, and abolishing the Junta. There are also demands around the gender-violence emergency. There are very high numbers and there’s a high correlation between economic depression and gender violence. If the man is constructed under machismo as being the bread-winner and there are no jobs, you’re no longer a man. This correlation has been studied; when economic depression comes, a way of expressing masculinity is by submitting the other to your power. There’s a huge gender-based emergency in Puerto Rico.

Another demand is to repeal the new labor reform, which enables employers to hire employees for a “trial period” of six months after which they can lay you off without any reason, benefits or compensation. This was one of the many neoliberal laws that were passed to supposedly revive the economy. One of the demands is to regain job security and to strengthen unions.

The more radical groups are saying- and we agree- that even if it cannot happen now, we should at least throw the idea out there to create asambleas del pueblo, popular assemblies. This generation knows that they have political power. If we reach a critical mass, we can turn government towards us and negotiate. If people start popular assemblies, we can start thinking “can we do a provisional government?” “Can we do a transitional government?” Because we know it’s not enough that he resigns. We have to stop every contract that this corrupt government has made, and that we already know are illegal. Not only that, we need to make those people pay. We need to bring criminal charges against them and restitute all that money they’ve stolen. One of the demands is to restitute that money back to the public books, las arcas publicas.

Juanqui: We have experienced a democratization process. We are talking of maybe a million people who took action or somehow participated throughout Puerto Rico. Imagine the proportions, almost 1 in 3 people. How can we keep this democratization process going? That’s where JunteGente wants to put its energy. We have to do that through direct democracy, like the assemblies, but also in making representative democratic processes more democratic and transparent. Pushing for those reforms while trying to expand those non-reformist reforms…

Science for the People: What about the status question? From the outside, it seems like the status question didn’t play a central role. Is that accurate?

Juanqui: that is totally accurate and it’s integral to many people’s political work including ours as JunteGente . The status question has been the black hole of radical politics in Puerto Rico. Our colonial relation to the United States is obviously crucial to our political context. That is crucial to recognize and not diminish that it but, as you just said, these protests were not about the status question. They were an intersectional popular uprising about race, class, gender, our bodies. Even though, yes, the Puerto Rican flag was everywhere in all its colors: the Resistance flag, the rainbow colors, the traditional colors, and so on.

Bernat: I think it [the non-centrality of the status question] was not instinctive or spontaneous but rather there was a conscious move towards that. The first big manifestation on Monday, July 8th was from the Capitol to the Governor’s Mansion. It was convened by Victoria Ciudadana, which is a new party for social justice that has no official position on the status question. In doing so, it is trying to disassociate radical politics from the status question because, as Juanqui says, there’s been a collapse between the independent movement and leftist politics as if they were the same thing—-which they’re not. There are very conservative people who are pro-Independence and by doing that collapse we are preventing ourselves from tapping into radical people who are pro-statehood or have other status ideologies. It is a black hole in the sense that radical social justice movements cannot grow beyond the traditional nationalist Left because of that collapse. So this party has been key in separating those aspects. Even though they were the convening voice in that specific manifestation, they did not bring ANY of their own party flags. They did not do a political hearing. When I arrived I saw about six flags of the independence party and my first reaction was: why do they do this? They did not convene it. This is a movement of the people. And people called them out, signaled it…and for the following manifestation, no one brought their flags. The organizations reached a consensus that this was simply not the time to bring out your organization flags. It was a march of the Puerto Rican people and I think that was KEY to your question of why people kept coming. This was different.

Juanqui: Victoria Ciudadana is just beginning. They’re not massive. Over the past decade, there have been different political attempts to go beyond the status question around social justice and bi-partisanism (which is actually a tri-partisanism) in which all parties are defined by their status position regarding the US. The problem with that is that people align according to status question and forget about all the policies that work against it.

One of the things we try to change is precisely the use of terms. For example, “soberanía”: the independence movement uses the term soberanÍa. We try to say “ok but let’s look at the different kinds of soberanías: food sovereignty, soberanías del pueblo, bodily sovereignty, energy sovereignty, etc. This allows people, regardless of where they stand on the status question, to relate to food sovereignty: “I want to grow my own food, I want my community to be able to have food and not need to depend on a chain”. Likewise to be able to relate to the feminist movement based on discourses of bodily sovereignty, reproductive justice, sexual sovereignty, the right to safe abortions, etc.

What’s happening now is the people’s sovereignty: regardless if we are a colony or not, this is popular sovereignty. Yes, under US rule but we are making radical transformations even under the current circumstances. Part of the discourse is “oh first we have to be independent and then we can do other things”. People are tired of waiting.

Continue Reading: ‘Mubarak On Our Mind’: The Popular Uprising in Puerto Rico Part II

View the complete video-recorded interview below.

The Boston chapter of Science for the People has passed through several stages since the rebirth of the organization on a national level in 2014. Currently, with the incorporation of new members inspired by the national convention in Ann Arbor in February 2018 and by politically oriented science events in Boston, the chapter has more than a dozen active members and many more who occasionally participate in chapter meetings. Most of the active members are associated with five universities around the city as students, post-docs, or faculty and represent a range of disciplines, such as physics, mathematics, oceanic and atmospheric sciences, bioengineering, public health, history and philosophy of science, with a few journalists, editors, and others not affiliated with universities.

The Boston chapter of Science for the People has passed through several stages since the rebirth of the organization on a national level in 2014. Currently, with the incorporation of new members inspired by the national convention in Ann Arbor in February 2018 and by politically oriented science events in Boston, the chapter has more than a dozen active members and many more who occasionally participate in chapter meetings. Most of the active members are associated with five universities around the city as students, post-docs, or faculty and represent a range of disciplines, such as physics, mathematics, oceanic and atmospheric sciences, bioengineering, public health, history and philosophy of science, with a few journalists, editors, and others not affiliated with universities.