A look back at the archives of Science for the People and its writings on the occupational health and safety movement in the United States.

Gail Robson & Taylor Lampe, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health

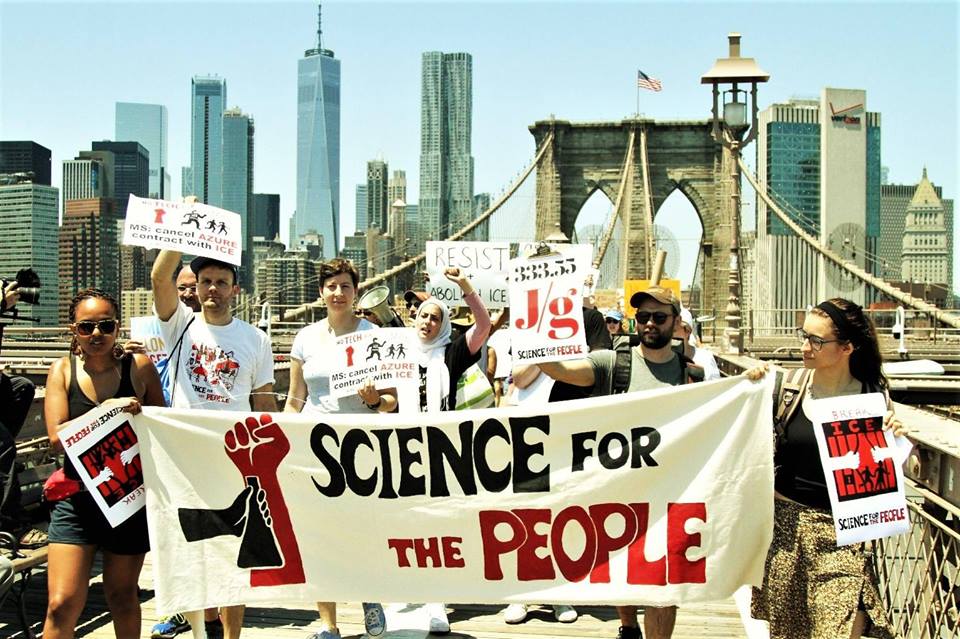

Science for the People’s publication began in 1969, and the Occupational Safety and Health Act (also known as OSHA) passed in the United States in 1970. The radical science movement in the US developed alongside the workers’ movement for occupational health and safety, and these early 20 years of collaboration are documented throughout the pages of the Science for the People magazine.

1980, Vol 12 No. 2

1980, Vol 12 No. 2

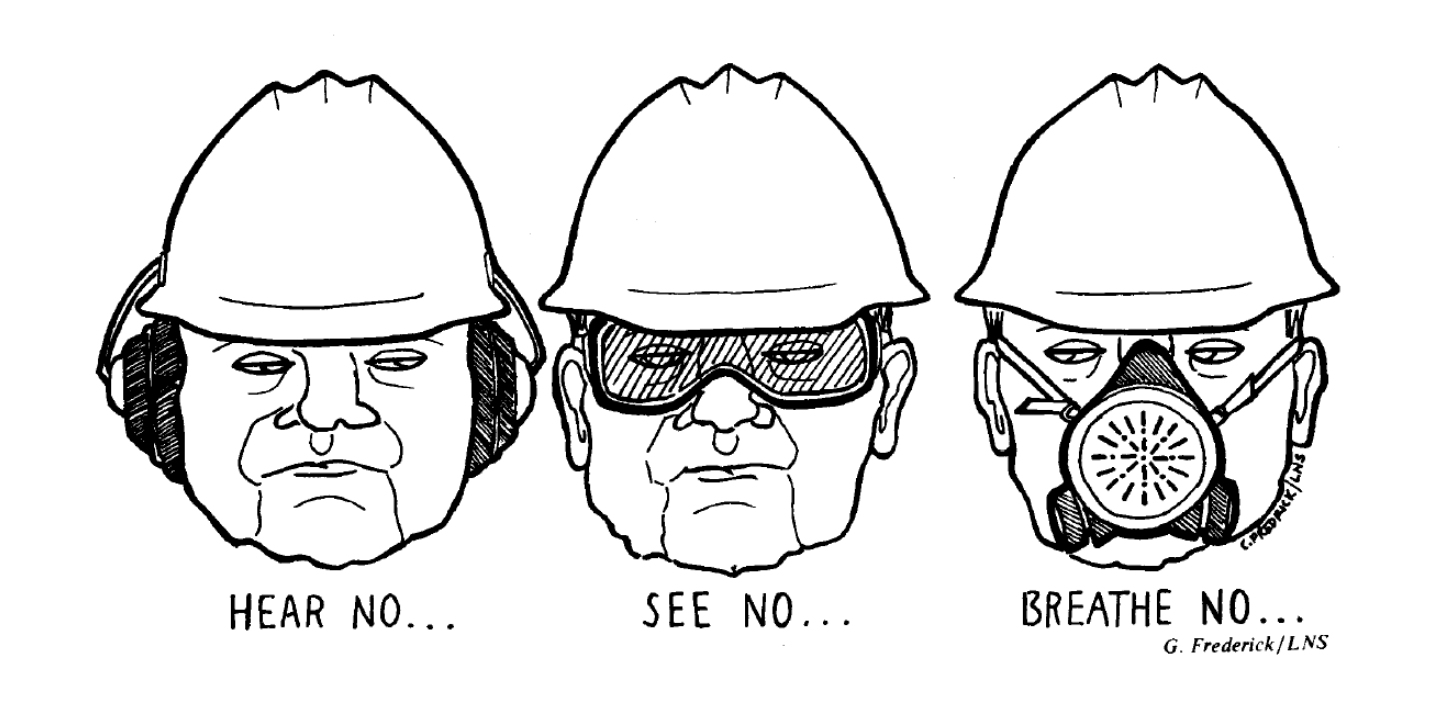

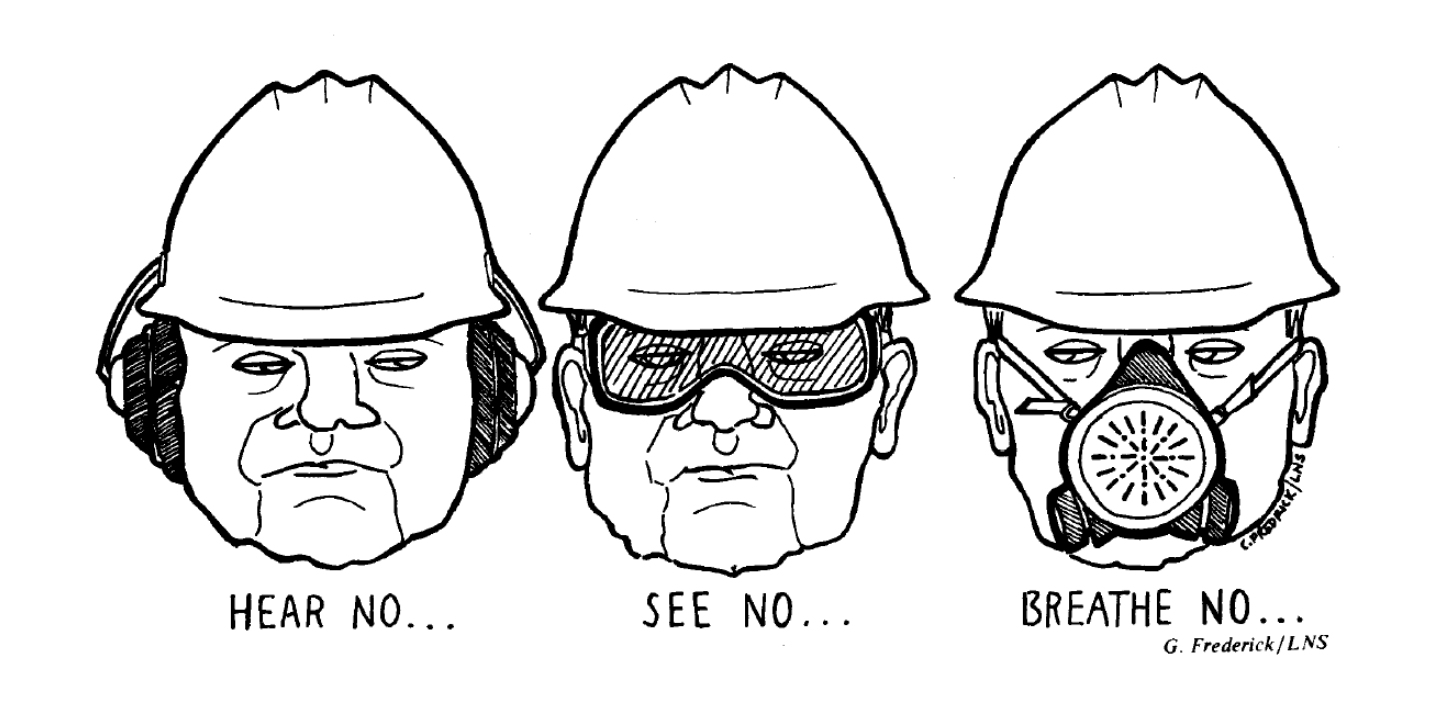

OSHA’s establishment in 1971 marked the first US federal legislative protection for workers’ safety, but many on the Left felt that the regulations were vastly insufficient. As argued in OSHA Inspectors, published in 1975, OSHA was merely “a capitalist reform program administered in the interests of the ruling class”, with no power, including money, staff, or enforcement, to force corporations to take the steps necessary to improve safety and health. In a 1974 speech, Midwest Workers Fight for Health and Safety, Carl Carlson detailed how corporations could work around OSHA to avoid providing protections for their workers. Dave Kotelchuck, in 1972 in Industrial Health and the Chemical Worker, called it a law “overwhelmingly biased in favor of management”.

RAISING LEFT CONSCIOUSNESS

The passing of OSHA, combined with increased workers’ calls for safety, coincided with the New Left’s increasing “desire…to relate to workers”, further claimed Kotelchuck. Although workers and unions had a rich history of organizing around occupational health and job safety, the early 1970’s critiques from the American Left marked the beginning of this issues as a ‘hot topic’ for the Left, he claimed. In his 1972 article, Kotelchuck hypothesized that the delay was influenced by the “tired old American myth” that workers were only concerned with wages and fringe benefits, rather than safety and health conditions. This, of course, was never true. As argued by Kotelchuck’s 1975 article, Asbestos: Science for Sale, workers have always been forced into the impossible choice between their jobs and their health. Many continued to choose work to support their families, at the literal costs of their mental health, physical health, and in many cases, lives, after daily exposure to harmful chemicals and unsafe environments.

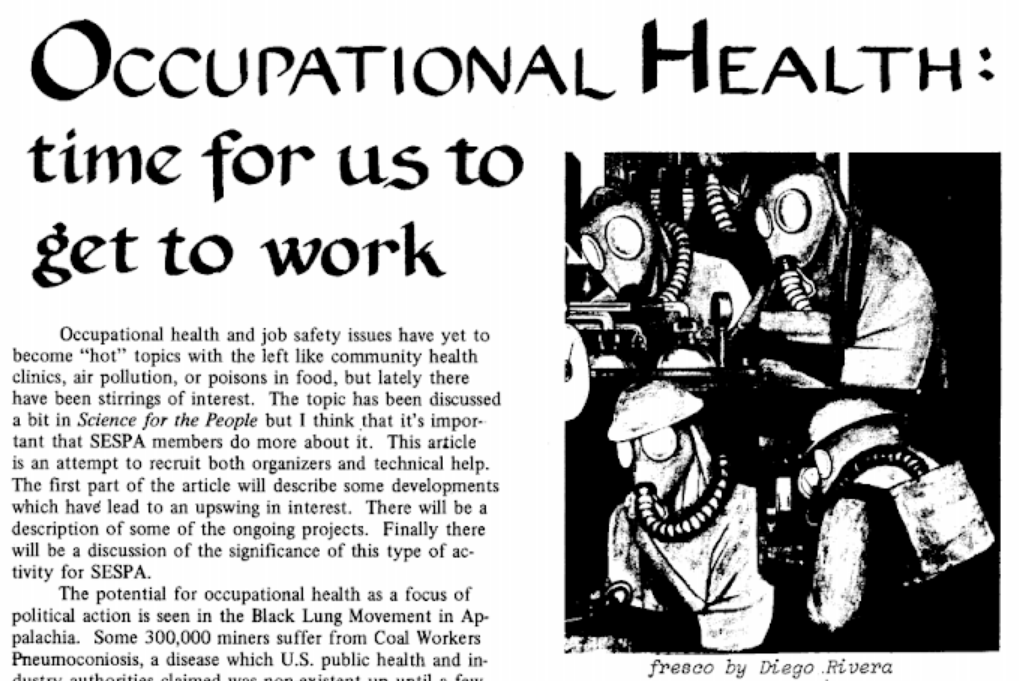

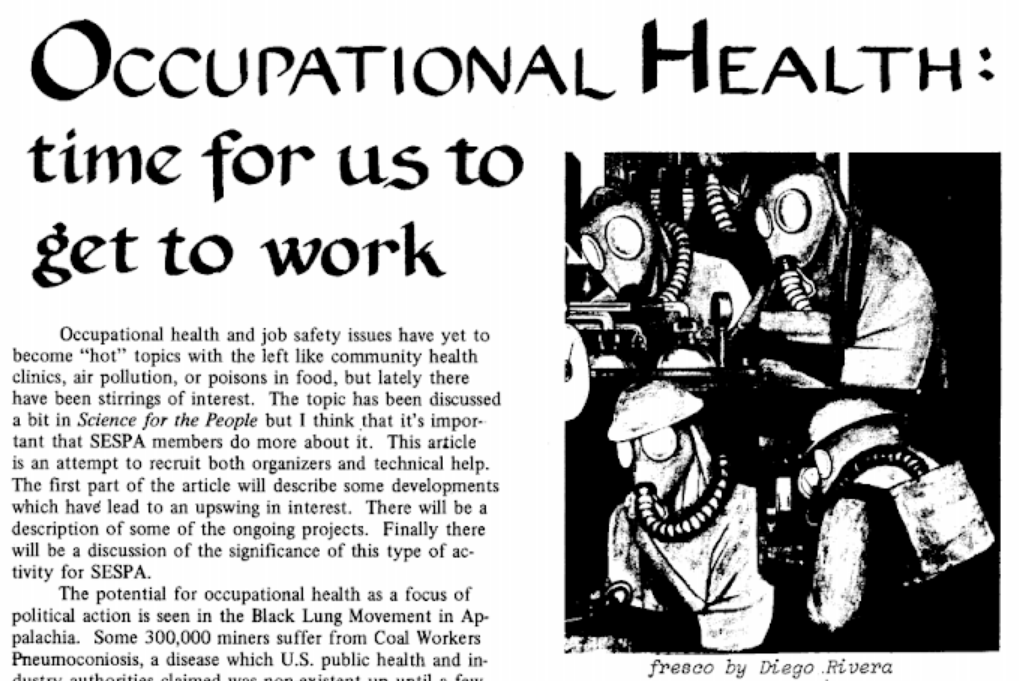

Frank Mirer, in a 1972 article titled Occupational Health: Time for Us to Get to Work, indicated that the Left saw this issue as one with the “potential for setting people, [especially industrial workers] into motion in a progressive direction”. Occupational health struggles, Kotelchuck also agreed, could serve as “the seed of worker control over the entire work process… and an important transitional step toward restructuring our society”. It was envisioned, in the face of weak legislative protections, that collaborations between radical scientists, workers, and unions could be used to improve objective working conditions, and also aid the entire Left movement in the process. The workers rights avenues created by OSHA could be strategically employed, as explored in Using OSHA, written by Chip Hughes & Len Stanley in 1977.

1972, Vol 4 No. 6

1972, Vol 4 No. 6

MOBILIZING SCIENCE WORKERS

Until the Left became more engaged with this specific worker’s fight, as Kotelchuck articulated, “previously, [radical scientists] had been no more aware [of occupational health issues]…than most people of similar middle-class background”. Science for the People membership in the 1970s consisted mostly of educated and technically trained, middle class scientists and engineers working in academia and industry. Many coming out of the American scientific education had little formal training on the socio-economic considerations of their technical work, as explored in a 1977 article Brown Lung Blues by Michael Freemark. In 1971, a union-organized gathering of 50 workers and scientists brought these scientists to a chemical plant, which for most, was the first time they came face-to-face with industrial working conditions. It was written that “the conference was an eye-opener”.

This disconnect, between the class and educational experiences of workers and radical scientists, posed challenges and opportunities going forward. Scientists were clearly, according to Mirer, “Outside the class or cultural background of the constituency they hope to serve”. They needed to, first and foremost, educate themselves. Few had specific training in occupational health. And many of the professional occupational health workers, like those hired by OSHA, were not primarily interested in the well-being of workers, and were not organizing with SFTP.

SFTP & UNION COLLABORATIONS

The SFTP magazine called for radical scientists to educate themselves, then use their technical skills to address this important issue. Scientists could engage in “service projects in this area” or “technical assistance projects” on top of their paid, daily work. A 1975 introduction to a special issue on Occupational Health and Safety made this statement:

“We are aware that as long as capitalism exists workers will be exploited by those who wish to maximize profits, and workplaces will remain unsafe… We urge more of our readers to… participate in the difficult task of finding ways to employ science to serve the health and safety needs of workers.”

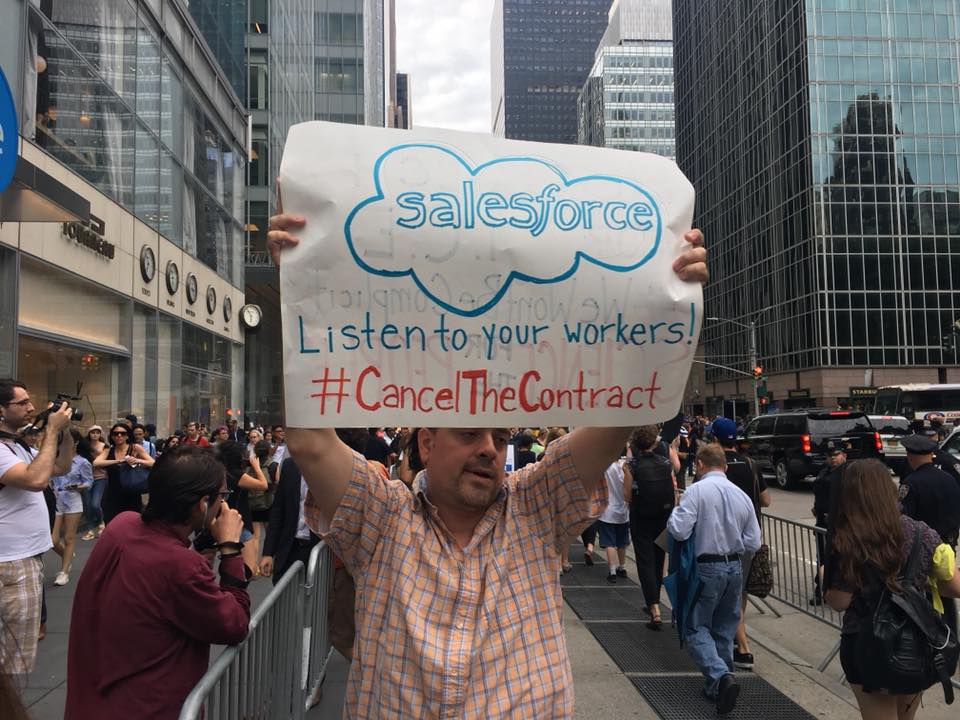

The foundation of this work for radical scientists would come from contacts with local unions and workers, both for educational reasons, and for organizing strategic reasons. Kotelchuck, in his 1972 article, claimed that “companies frown on contact between science workers and production workers” because they wanted to keep workers unaware of their health and safety risks. A pamphlet published in 1974, How to Look at Your Plant, empowered workers to cite violations and take action. Then, in collaboration, scientists could provide workshops on physiology, chemical exposures, and safety protections. They could train workers to perform air and temperature tests, set up health clinics, or perform epidemiological studies if little was known about the exposure. Unions and workers could then use this information, and the small workers’ rights offered through OSHA, to document and hold more management accountable to safety and health violations.

1974, Vol. 6 No. 4

As these alliances turned into more formalized coalitions, the COSH movement, or regional coalitions or committees for occupational safety and health, was born in the US. The primary role of COSH groups were for scientists, labor unions, health, and legal professionals to support worker struggles concerning health and safety issues through technical assistance and empowering forms of education. Organizing for Job Safety by Dan Berman in 1980 detailed the history of the movement starting in 1972; Education and Research in Occupational Health in 1982 described the connections of these groups to academics and scientists; Knowing about workplace risk, by Dorothy Nelkin & Michael Brown in 1984, acknowledged the essential role played by COSH groups in knowledge dissemination and education to workers.

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH OF WOMEN

A theme that emerged throughout the decades of publishing within the realm of occupational health and safety was a focus on the occupational health of women, and the critique of US policies enacted ostensibly to help women workers. Generally, these policies were not enacted to protect the needs of women themselves, rather they protected, or claimed to protect, their reproductive capacity and the babies they could potentially be carrying. For example, the 1980 article Danger: Women’s Work described factories with high levels of toxic exposure banning women of reproductive age from working there at all, rather than insisting on an environment that was safe for everyone. As a result of these policies, many women felt forced to go through sterilization to keep their jobs.

In 1980, Your Body or Your Job, by John and Barbara Beckwith, argued that sexual harassment in the workplace was an essential occupational health issue, and one neglected by the feminist movement. The term “sexual harassment” itself did not exist until 1975 and at the time of publishing this article, the only legal precedents were at district court levels, including a ruling in 1976 that sexual harassment was violation of title VII sex discrimination clause of Civil Right Act. This article acknowledged that Black women were the most vulnerable to sexual harassment, while simultaneously these women often took on leadership positions on the issue and brought forward the greatest number of lawsuits around the US. The writers called for the struggle against capitalism and patriarchy to carry on side by side, since anti-capitalist work alone would not be sufficient to also tackle patriarchal oppression in the workplace.

1980, Vol. 12 No. 2

1980, Vol. 12 No. 2

WORKER RIGHT-TO-KNOW

Another major advocacy activity by SFTP was for workers’ right to know the hazards of substances with which they were working, and pushing for the enactment of state-level right-to-know legislation. In Knowing about Workplace Risks, Dorothy Nelkin and Michael Brown described the complex barriers preventing workers from information around their own safety, and how some workers effectively obtained information in their own workplaces. Mandy Hawes, in Dying for a Job in 1980 documented trends in chronic Benzene exposure and leukemia and put forward suggestions for organizing by documenting health effects in the workplace, and the protection measures that exist, while calling for hazard evaluations and standard-setting at a federal level along with state-level legislation. Asbestos and the chemical sterilizer DBCP were also key issues in right-to-know advocacy in the 80s, as described in the 1982 articles, Keeping Workers in Line, and Asbestos in the Classroom.

Chris Anne Raymond in the 1984 article, Whose Health and Welfare, critiqued the mainstream press as treating disease revelations “like natural disasters, a sudden and unforeseeable accident, to which the industry and government responded wisely and forthrightly” while in reality these risks were embedded in the system of production, and industry and government had no incentive to protect workers without strong union opposition.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Science for the People publications ended in 1989, and since then, many of these themes are ongoing today. Work environments and hazards continue to change as industries and technologies develop, and as the labor movement changes, there is a continued need for sustainable collaborations between radical scientists, workers, and unions. Future articles and publications can further engage with the gendered and racialized aspects of occupational health and safety, and reflect on how the field has changed over the past decades.

Authors: Gail Robson and Taylor Lampe, MPH Students at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health

ALL ARTICLES

Vol. 4 No. 3: “Industrial Health and the Chemical Worker” by Dave Kotelchuck (1972)

Vol. 4 No. 6: “Occupational Health: Time for Us to Get to Work” by Frank Mirer (1972)

Vol. 6 No. 4: “Midwest Workers Fight for Health and Safety” (speech 3/16 by Carl Carlson at “Workers’ Forum on Safety and Health” in Chicago, 1974)

Vol. 6 No. 4: “How to Look at Your Plant” (1974)

Vol. 7 No. 5: “About this Issue: Occupational Health and Safety” (1975)

Vol. 7 No. 5: “Asbestos: Science for Sale” by David Kotelchuck (1975)

Vol. 7 No. 5: “OSHA Inspectors” by Anonymous (1975)

Vol. 9 No. 3: “Brown Lung Blues” by Michael Freemark (1977)

Vol. 9 No. 5: “Using OSHA” by Chip Hughes & Len Stanley (1977)

Vol. 12 No. 2: “Dying for a Job” by Mandy Hawes (1980)

Vol. 12 No. 2: “Danger: Women’s Work” by East Bay SFTP (1980)

Vol. 12 No. 4: “Organizing for Job Safety” by Dan Berman (1980)

Vol. 12 No. 4: “Your Body or Your Job” by John Beckwith & Barbara Beckwith (1980)

Vol. 14 No. 1: “Education and Research in Occupational Health” by Luc Desnoyers & Donna Mergler (1982)

Vol. 14 No. 4: “Keeping the Workers in Line” by Heidi Gottfried (1982)

Vol. 14 No. 4: “Asbestos in the Classroom” by Nancy Zimmet (1982)

Vol. 16 No. 1: “Knowing About Workplace Risks: Workers Speak Out About the Safety of Their Jobs” by Dorothy Nelkin & Michael Brown (1984)

Vol. 16 No. 4: “Whose Health and Welfare: The Press and Occupational Health” by Chris Anne Raymond (1984)

The Boston chapter of Science for the People has passed through several stages since the rebirth of the organization on a national level in 2014. Currently, with the incorporation of new members inspired by the national convention in Ann Arbor in February 2018 and by politically oriented science events in Boston, the chapter has more than a dozen active members and many more who occasionally participate in chapter meetings. Most of the active members are associated with five universities around the city as students, post-docs, or faculty and represent a range of disciplines, such as physics, mathematics, oceanic and atmospheric sciences, bioengineering, public health, history and philosophy of science, with a few journalists, editors, and others not affiliated with universities.

The Boston chapter of Science for the People has passed through several stages since the rebirth of the organization on a national level in 2014. Currently, with the incorporation of new members inspired by the national convention in Ann Arbor in February 2018 and by politically oriented science events in Boston, the chapter has more than a dozen active members and many more who occasionally participate in chapter meetings. Most of the active members are associated with five universities around the city as students, post-docs, or faculty and represent a range of disciplines, such as physics, mathematics, oceanic and atmospheric sciences, bioengineering, public health, history and philosophy of science, with a few journalists, editors, and others not affiliated with universities. 1980, Vol 12 No. 2

1980, Vol 12 No. 2 1972, Vol 4 No. 6

1972, Vol 4 No. 6

1980, Vol. 12 No. 2

1980, Vol. 12 No. 2