Report from SftP Delegation to Cuba

We left Havana on May 3. Tired after days of seminars, meetings with locals, and cultural activities, I was able to begin unpacking and relax, unlike many others returning home to the United States who ended up being detained at the airports of Miami, Ft. Lauderdale, and Newark. They were granted special permission to visit Cuba under the US blockade that has been in place for more than sixty years (except for a short reprieve from 2014–2017). Yet, despite legal documents and US citizenship, the border agents harassed, threatened, and abused them like criminals. Freedom of movement does not apply to people in the land of the free.

With the recent addition of Cuba to the “State Sponsors of Terrorism” list under the Biden administration, the economic barrier erected by the most comprehensive blockade in history serves more than to asphyxiate Cuba into submission; its primary goal is to prevent the world from seeing and believing in an alternative to capitalism. Fredric Jameson once said that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. He must have not visited Cuba.

Don’t get me wrong. Cuba is not a utopia. It is visibly struggling; infrastructure is crumbling; economic inequality exists; Cuban people are far from happy or content and some aspire to find new lives abroad. Nevertheless, what we learned in our ten-day trip in Cuba is that the left in the Global North cannot address the various issues facing us today without learning from the Cuban experience. To do this, and to concurrently strengthen anticapitalist struggles across the world, we must first and foremost break the US blockade on Cuba.

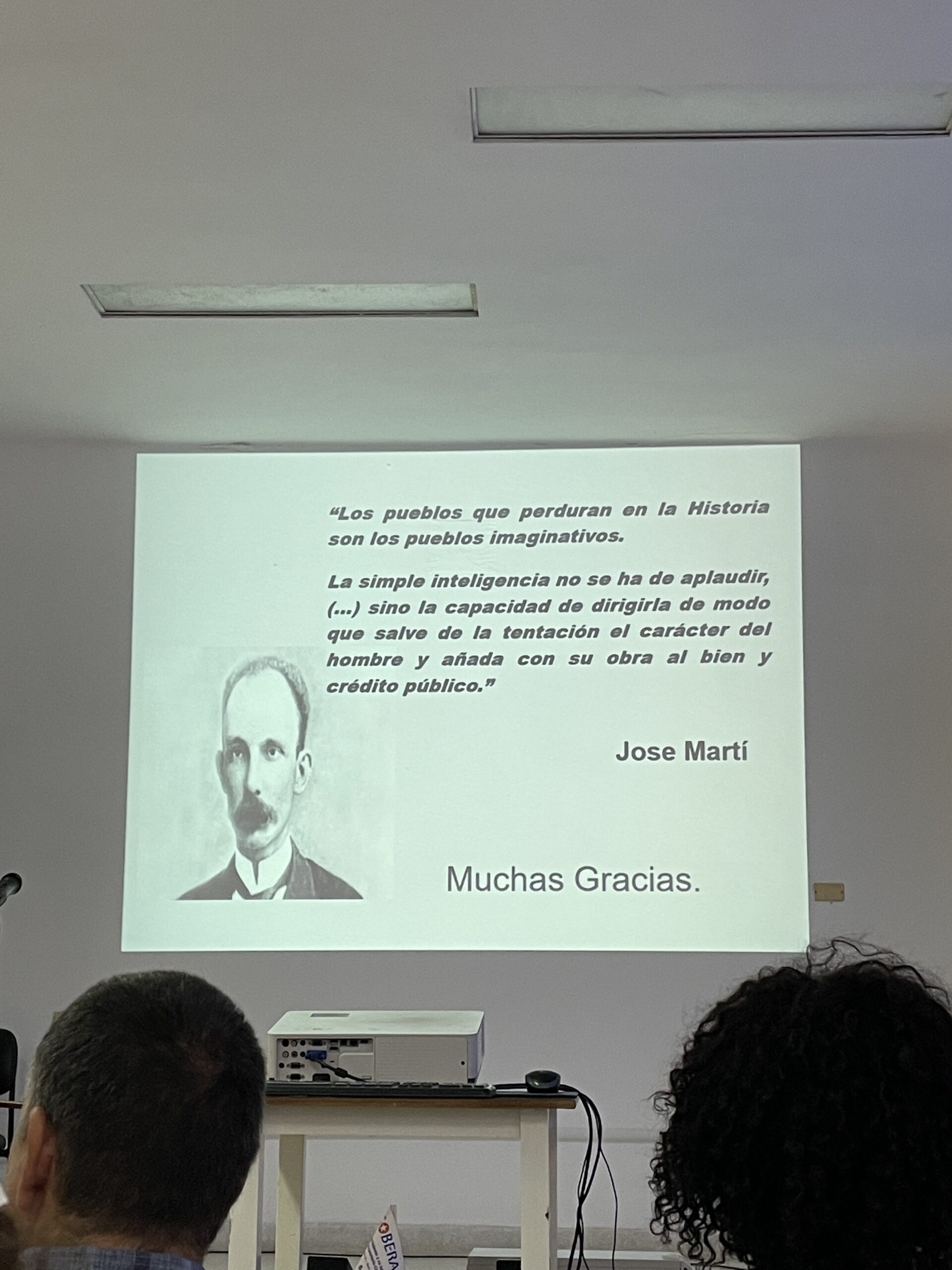

Phenomena do not exist in isolation. The US blockade must be recognized as a manifestation of the same colonial project that existed long before the Cuban revolution of 1959 and the Cuban independence movement of 1902, as this year marks the 200th anniversary of the Monroe Doctrine. One misconception about Cuba is the association with a singular figure of Fidel Castro. While many ordinary Cubans profess their love for their Comandante el Jefe, Fidel’s name or image is hardly seen in Havana—it was Castro’s own wish that public commemoration be discouraged. If there were to be a personification of the Cuban psyche, it is poet and anticolonial fighter Jose Martí. More than anything, Cubans pride themselves with the progress they made in anticolonial, anti-imperialist struggles since Martí. Seeing from the outside, the Cuban people today objectively retain degrees of sovereignty above neighboring states like Haiti, Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico (which remains a US colony). In real terms, while Hurricane Maria left nearly three thousands people dead in Puerto Rico and devastated the island for years, Cuba suffered few casualties and quickly rebuilt—a fact undeniable even by the Washington Post. Thus, the question of whether Cuba is a socialist country matters less than whether Cuba is able to overcome centuries of colonialism. At the same time, the former is directly related to the latter: its socialist principles are in lockstep with its national liberation project.

If you are an astute observer, you may pick out these principles traveling through Cuba. We did not need government officials, union representatives, or prominent intellectuals to tell us what they are. The lack of advertisement even at the busiest tourist corner of Havana reflects the social constraints exerted on market forces. The complete lack of police presence, even at 2 a.m. in an area with vibrant nightlife, the absence of homelessness, loitering youth, panhandling, and general wretchedness speak loud and clear about human welfare and security. Even when the buildings and sidewalks are in disrepair, music, art, and people in the community filled the public spaces. And of course, the hospitals—the successes of the Cuban healthcare system in taking care of its own people need no further elaboration. Lesser known is Cuba’s leading role in global health. We visited Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina (ELAM) and met students from Congo, Chile, Palestine, and the United States (who came from underserved communities) on full scholarships; these students are trained with the socialist philosophy that sees health not as a mere biological problem but also a social issue, which prepares them to be able to serve their own community upon completion of training by gaining an understanding of their own geographical, political, and cultural contexts. This act of internationalism is but a small part of the renowned Cuban medical brigade that provides humanitarian aid to all corners of the world—to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, Africa during the Ebola outbreak, Syria after the recent earthquake, to name only a few.

Claudia, a young woman we met during the visit to Centro de Inmunología Molecular (CIM), was among the medical volunteers at the peak of COVID-19 infection. She was not a physician but a scientist working on the now-approved SOBERANA vaccine. As the US blockade deprived Cuba access to the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines, they had to develop their own. After devoting hundreds of hours in the labs producing the basic research before vaccines can be mass manufactured, she spent months in Venezuela educating local communities on public health measures and helped distribute the million doses of SOBERANA donated from Cuba. We were deeply moved by such an embodiment of science in the service of humanity. It’s important to acknowledge that not every Cuban medical or science student is like Claudia—she told me as much; many trainees have left the country in pursuit of higher pays as physicians and scientists, and many are quitting their education to earn hard currency from the nascent tourist industry. The realization that we are the tourists still haunts the memory of this encounter. Meanwhile, Cuba’s pharmaceutical development is not entirely humanitarian, as SOBERANA under international patent rights allow for its sales and distributions in higher income countries to boost Cuba’s export. The market still dictates many facets of Cuban life.

I am reminded of Huey Newton’s famous phrase: revolution is a process. If we simply take Cuba’s achievements in medical internationalism, scientific achievement, as well as the new 2022 Family Code that granted unprecedented rights to women, elderly, and LGBTQ+ communities—a demonstration of popular democracy through which millions of votes were casted and thousands of debates, consultations, and public events were held—as discrete victories of progress, we may find exemplary counterparts in Western Europe. But seeing the Cuban society as an agent in world history, we can draw a few unique lessons for our own struggle to overcome capitalism.

First, we must study and understand how Cuba survived adversity, not just building a national and cultural identity on a resource-deprived island ninety miles off the coast of a settler-colonial empire, but actively resisting continued imperial aggression after centuries of slavery and extraction from the United States. In prioritizing human development as official policy, Cuba stands out among countries in the world for its education, medicine, science, sport, and arts. We may disagree on the verity of its socialism, but none can deny the contribution to humanity that the Cuban people have made since 1959 in healing and defending the world against colonists in Algeria, Angola, and Vietnam, etc.

Second, in studying the contradictions, problems, and challenges of Cuban society, the effect of the US blockade cannot be underplayed. Any commodities that comprise 10 percent or more manufacturing in the United States are restricted to enter Cuba; third party countries or private firms that attempt to establish trade with Cuba will need to constantly tiptoe around sanctions and fines from unilateral US law, the content of which changes regularly to discourage capital influx to Cuba. As a result of economic suffocation, Cuba’s energy and food supply are in tight balance, always in conflict with social expenditure. We experienced several blackouts during our stay, and by the end of the trip became accustomed to sudden changes of itinerary due to logistical issues. While it is all the more impressive of what Cuba was able to achieve under the blockade, it should lead us to contemplate what more would Cuba have provided to the world if it is freed from the US stranglehold?

Third, capitalism and imperialism are coevolutionary processes. We cannot win class struggle in the advanced capitalist countries at home without solidarity from the Global South—the majority of the world. This is where Cuba stands tall as a beacon of anti-imperialism since the beginning of the revolution, with its illustrious legacies of vanguarding the formations of Organización de Solidaridad de los Pueblos de Asia, África y América Latina (OSPAAAL) and the Non-aligned Movement. As the blockade not only hinders social/socialist development of Cuba and the rest of the Third World, it is a detriment to our struggles in the metropoles. On a superficial level, we ask how many lives would be saved if the Cuban Heberprot-P treatment for diabetic foot ulcer or CIMAvax-EGF for lung cancer are allowed for the hundred million poor people in the United States? At a deeper level, if the US rulers can continue to disregard the will of the world’s people and commit to carry out this crime against humanity, what would they do to nascent revolutionary struggles in other parts of the world (e.g., Venezuela, Palestine), or under its own belly (e.g., Black and Indigenous liberation)? The Cuban sovereign project, socialist or not, is at the forefront of a totality of world struggle against capitalism and empire.

At the end of this write-up, our comrades detained at the US border are now released. They told us that their phones were immediately seized, broken into, while being denied legal consultation. We went on a trip to learn about Cuban society. Perhaps we learned just as much if not more about our own society. In order to free ourselves from repression in our own country, we must stand in solidarity with the Cuban people suffering from the same repression manifested abroad. The blockade against Cuba is a blockade against our own future, a shared vision by the people of the world fighting for peace, justice, and all that is good of humanity.

—

In the coming months, SftP will produce more content related to our trip to Cuba as we launch campaigns to #EndtheBlockade.

Between January and April 2021, Science for the People co-organized a reading group along with DSA Ecosocialists and The Dig podcast of Thea Riofranco’s “

Between January and April 2021, Science for the People co-organized a reading group along with DSA Ecosocialists and The Dig podcast of Thea Riofranco’s “